24 FIDDLE CLASSICS (VINTAGE 60s) RHY-286

Liner notes by Barry R. Willis 2003

Rosin up the fiddle and tighten up the bow. We’re gonna have a hoedown.

You won’t be able to keep your feet still when you play this compact disc. It’s loaded with familiar fiddle favorites with the traditional versions to which you’ve become accustomed. Any aspiring fiddler needs this recording in order to pick in the parking lot of any bluegrass festival or fiddle contest.

Fiddle champion DeWayne Ware includes his own The Great Ware Family band. He uses the proper combination of “short-bow” fiddling to give us the feeling that we’re at the hoedown and ready to hit the floor for the first dance. This fiddler combines all the best in tone, timing and tricks on this recording.

We start the tunes with the ever-popular “Cotton Eyed Joe” and followed by familiar tunes such as “Cripple Creek,” “Chicken Reel,” “Soldier’s Joy” and twenty others.

It’s easy to see why the owner of Rural Rhythm Records, Uncle Jim O’Neil, wanted to record these folks. DeWayne and company simply “lay it down” as it should be done.

There’s only one phrase to describe this recording: “Yee Hah!!!”

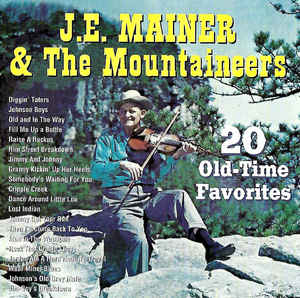

J.E. MAINER AND THE MOUNTAINEERS “20 Old-Time Favorites” RHY-250

Liner notes by Barry R. Willis

The music of the legendary J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers will live forever. It will be with us not because some record company wants to make a buck from reproducing it and putting it up for sale, but because the music is just plain good! Rhythmic and often exciting, this old-time country music gives us a window to the past, providing us an idea of just why this kind of music was unconditionally loved “back in the old days” by the rural folks of the Carolinas. Though crude by some of today’s standards, this is pure, old-time country as it was played in the 1930s: wholesome, authentic and worthy of a listen. But don’t just listen to it, absorb it and try to imagine the fun these folks were having.

Wade Mainer, J.E.’s brother and a founding member of the Mountaineers in 1934, recently commented that J.E.’s music never changed through the years (neither did Wade’s for that matter). This recording, a compilation of J.E.’s recordings through his many years with Rural Rhythm Records during the ‘60s and ‘70s, is some of his best stuff. Some of the excitement of J.E.’s live performances comes through on this recording.

J.E. recorded for many labels through the years, but some his most inspired recordings were recorded on Uncle Jim O’Neal’s Rural Rhythm label. Uncle Jim only recorded the music he loved. He let his artists record their own music without external influence from some fancy recording producer at a larger label who might try to manipulate the artist’s music so it would sell to the “mass” audience. O’Neal wasn’t overly concerned about the profit a recording could make, only that their music be preserved in all its authentic glory.

In addition to J.E.’s wonderful old-time sound, we can, on many of these songs, hear the modern bluegrass banjo and the smooth, contemporary singing of Morris Herbert. This adds a different flavor to J.E.’s music, making it more “up-town” and palatable for those seeking the more progressive sound of bluegrass music which, when we recall the history of bluegrass, actually wouldn’t come along until the decade after J.E and Wade formed the Mountaineers. According to J.E. Mainer Jr. (J.E.’s oldest son) in a 1998 conversation, his father hired the members of the Mountaineers because they had a knack and a love for his music. Indeed they did, even the “bluegrassy” Morris Herbert came around to what J.E. taught him. It was good and, as we can tell because you have this recording in your hand, it was long-lasting. Here is a biography of the Mainer brothers, J.E. and Wade.

Joseph Emmett Mainer was born July 20, 1898; Wade Mainer was born April 21, 1907. The brothers were born in Weaverville, near Asheville, Buncombe County, North Carolina. J.E. took up the fiddle, learning from brother-in-law Roscoe Banks, and also played a little frailing banjo. His first fiddle was a miniature, obtained as a prize when he and Wade sold the most of a popular salve during a sales contest. He became pretty good on that little instrument and in the early 1930s went downtown to buy a full-sized fiddle which cost $9. In 1910, at age twelve, J.E. left home to work in the cotton mills of Knoxville, Tennessee. Wade was three.

Wade recalled, “I was workin’ in the sawmill around about eleven or twelve years old and I guess I stayed with it for two or three years ‘cause my dad didn’t have much to do back there on the farm. And he give me about fifty cents a week to go a picture show or something.” This may not sound like a lot of money, but in those days fifty cents could buy a week’s groceries for a small family. The fact that kids got any spending money was kind of unusual. As Wade’s career continued into the Great Depression of the mid-1930s, an admission charge to his concerts of fifteen and twenty-five cents was a lot of money to people in rural America who could barely feed themselves. It’s no wonder that Wade quit being a full-time musician in the early 1950s to try to find a “normal” job which would provide some sort of security for him and his family.

An important part of the Mainer sound was Wade’s two-finger banjo playing. “Really, what started it all,” told Wade, “was when I worked with my brother-in-law, Roscoe Banks, at the sawmill when I was ten or twelve years old. I was just a young fella growin’ up on the farm down in Weaverville, North Carolina, and we lived on Rim’s Creek. So my brother-in-law had a sawmill and I would go stay with him and he played the fiddle. On Saturday evenings they’d shut down the mill and go get cleaned up good and get ready for a square dance that night. Somebody was always wantin’ some music to play for square dances back there in the mountains. So [Roscoe] had a brother by the name of Will Banks that played the banjo but he played the frailin’ type. It wasn’t very good time with the fiddle, you know. And I’d go set in with them at the square dances. When they’d lay the banjo down to get up and take a break, I’d go over and pick up the banjo and start hammerin’ down on it. I learned to frail a banjo first!

“And then, after awhile, I began to think I might just try it with my fingers and see what happens then. I got to meddlin’ with it—pickin’ it out note-for-note with my fingers. I kept on and got pretty good with it and got to learn to use my fingers to keep the time with it. It wasn’t very long—I guess it wasn’t over a couple of months learnin’ the two-finger style—and I was workin’ at the sawmill with him and after I got to where I could play the two-finger style. I kept better time with the fiddle and all, so my brother-in-law just kept me to play the banjo when he played the fiddle.”

Wade wrote that in the beginning “There were many times I wished [then] we’d never started playing music. For working in the cotton mill in the day, and J.E. at night would keep me up half the night or longer playing music. I’d get irritated, especially when he’d tell me to get up; he had a new tune he wanted to learn.”

By 1922, J.E. had moved to his permanent home in Concord, North Carolina, and married. He later began working as a musician. Wade was working at the Weaverville sawmill near Asheville. Will Banks played banjo with Roscoe at many square dances—the main source of entertainment in the mountains. “I guess, when I was about eighteen to twenty years old (about 1927), I left and started for Concord, North Carolina. I had an old banjo and I had it with me and I stopped off in Marion and got me a job workin’ at a yarn mill in Marion, North Carolina, and stayin’ in a boardin’ house. I’d get the old banjo out in the evenin’ and the boarders at the boardin’ house, they resented me playin’ the banjo—I was makin’ so much noise they couldn’t stand me. I worked there quite awhile then moved on down to Concord and that’s where I began to join up with my brother J.E..” This is where the brothers decided to make music professionally—J.E. on the fiddle and Wade on the banjo. The brothers won fiddle contests and began playing at corn shuckings and other social events. Wade told this writer, “We got so good at Fiddlers’ Conventions taking prizes they finally wouldn’t let us enter for prizes.” They became influenced by Gid Tanner and the Skillet Lickers, the Carter Family, Jimmie Rodgers, and Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers. In the latter part of 1933 or early 1934, J.E. and Wade called themselves the Mainer Mountaineers String Band.

“We were the first to have the bluegrass style—with the drive—’til it kindly got a little bit, I’ll say uptown, faster and higher pitched. And when it got into that, it kind of left the Mainer Mountaineers…” he told this writer in a 1992 interview. “I didn’t do too much lead on the banjo because we had the fiddle for a lead. Well, the fiddle finally faded out when Bill Monroe… Well, Bill wasn’t the first one to play the mandolin ‘cause the Tobacco Tags had the mandolin when we were working for Crazy Water Crystals back in ‘35 and ‘36. We had already established the mandolin, but when the mandolin (of Bill Monroe) came in, the mandolin took over the lead for the fiddle. But the mandolin style of Monroe was different,” said Wade. “Monroe’s style was pitched high, sung high, played high and they sung with a drive. We had that same drive when we recorded with Clyde Moody. There were two or three [tunes] that we had the fiddle and you can hear the banjo with the drive in it.”

Ralph Stanley was a banjoist who initially used the clawhammer style then picked up the two-finger style from Wade. Wade recalled that the Carters “was workin’ around the Bristol area when Carter and Ralph [Stanley] was just boys. So Ralph and Carter stayed around us a whole lot and learned a lot of our music. You can go back to some of the old recordings and find that they recorded a lot of songs that we already recorded. Ralph was just a little ol’ boy; him and Carter both, when I was workin’ professional.”

The Mainer brothers hired the Lay brothers, Lester and Howard Lay, in 1934, and they became J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers, working Saturdays on WSOC, Gastonia, North Carolina, on the “Wayside Program.” Then the group went to WWL for about four months in New Orleans, Louisiana. After the band returned to Concord, the Lay brothers left the Mountaineers to stay and work at the cotton mills. Soon Wade and J.E. were doing two shows daily at WBT, Charlotte, North Carolina, in addition to the WBT Barn Dance.

They hired Daddy John Love (guitar, yodeler in the style of Jimmie Rodgers, blues singer) and Zeke Morris (guitar). This was Zeke Morris’ first job as a musician. When he and his brothers, George and Wiley, later formed the Morris Brothers, they sounded similar to the Mountaineers. The popularity of J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers was enhanced with the addition of Love and Morris.

They played the music of the day: hillbilly music. In an interview with this writer in October, 1990, at the IBMA Trade Show, Wade Mainer said that Bill Monroe very well could be the “Father of Bluegrass Music” but said that both groups (the Mountaineers and the Monroe Brothers) were playing pretty close to the same kind of music during that period. Bill Monroe was still with his brother Charlie at the time and they used guitar and mandolin. The Mainers used banjo, fiddle and guitar.

When asked if the Mainers’ style was similar to other bands Wade remarked, “Yes and no. I don’t believe our style was quite like the rest of them…we didn’t hear nobody else playing our style of music. We had our own style and sound. I don’t think we was all that good (he laughed). But I’ll tell you one thing, our songs and records sure went over big with the good people.” Wade recalled the old days when they had to travel in a T Model Ford. Because the crowds were so great, they often had to play two shows to accommodate the audience which came on horseback, or by car, or walked up to six miles to hear them. He remembered that they were wonderful people to play music for.

About that time, the group gained Crazy Water Crystals as a sponsor and played on WBT, Charlotte, North Carolina, on the Crazy Barn Dance. The group changed its name to J.E. Mainer and the Crazy Mountaineers. Other groups sponsored by the company were the Dixon Brothers, Tobacco Tags, Fisher Hendley’s Aristocratic Pigs, Dick Hartman and his Tennessee Cut-Ups, and the Johnson County Ramblers.

Their personal appearances on WBT were sponsored by Crazy Water Crystals; the sponsor kept all the money and gave them only a small stipend. But the group did gain exposure and bookings from the shows—that’s where they made their money. Band members made twelve to fifteen dollars per week—actually a good wage; the band leader, of course, made more than the sidemen (who were generally hired by the leader to fulfill the leader’s idea of what his music should be). Wade quit the sonsor several times in an attempt to get a better cut of the profits. When the band finally split from their relationship with Crazy Water Crystals, they returned their name to J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers. As useful as the Crystals sponsorship was at one time, the band no longer tolerated the situation of getting only a portion of the gate receipts. Now on their own, they were able to keep the entire gate.

On August 6, 1935, J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers began recording in Atlanta, Georgia. This led to a recording contract with Bluebird, RCA Victor’s sublabel (a subsidiary of RCA) which handled this type of music. They recorded “Maple On The Hill,” a duet sung by Wade Mainer and Zeke Morris who had recently joined the Mountaineers. Wade felt that his arrangement was different enough from the original to copyright it. He also arranged and copyrighted “Take Me in Your Lifeboat.” Band members then were still Wade and J.E. Mainer, Zeke Morris and Daddy John Love. The June 1936 Bluebird session of J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers helped the group’s popularity to grow.

That October, J.E. and Wade Mainer split. J.E. kept the J.E. Mainer’s Mountaineers name with musicians Snuffy Jenkins (banjo), George Morris (guitar) and Leonard “Handsome” Stokes (mandolin). Just after the split, Wade and Zeke Morris joined with Homer “Pappy” Sherrill on another Bluebird recording. This band was unofficially called the North Carolina Buddies and lasted only a very short time. Then Wade founded the Smiling Rangers which consisted of Wade, Sherrill, Zeke Morris, Homer Sherrill’s brother Arthur, and Wiley Morris at WPTF, Raleigh, North Carolina. Pappy Sherrill stayed on fiddle from 1937 to 1938 when Wade quit his Smiling Rangers band to form Wade Mainer and the Little Smiling Rangers.

On April 15, 1937, J.E. Mainer and His Mountaineers were first heard on WIS (a part of the NBC network at the time) in Columbia, South Carolina. Though the station was then an infant of seven years, it was still rated the 38th most popular station in the U.S.. The Mountaineers’ daily show aired Monday through Friday. The band was at the station’s largest puller of mail; they received 8,305 pieces of mail during the six months from October 1937 to March 1938 without benefit of contests or free offers. They were sponsored on WIS by the Chattanooga Medicine Company. There at WIS was announcer Byron Parker.

In late 1938, J.E. left his Mountaineers. Byron “The Old Hired Hand” Parker of Wisconsin took over the group. Parker added Homer Sherrill on fiddle and called it Byron Parker’s Mountaineers. When Parker later took the band to WIS, it became the Byron Parker and the WIS Hillbillies with members Byron Parker, Snuffy Jenkins, Homer Sherrill and Leonard Stokes. Because they were sponsored by Black Draught, they became Black Draught Hillbillies and Homer Sherrill as well as Byron Parker’s Mountaineers. Byron Parker had considerable experience in the music business already. He was, according to Wade Mainer, “one of the best emcees you ever seen in your life. He could sell a barrel of rotten apples on the radio if he wanted to. He was that good!” He picked up the nickname “The Old Hired Hand” at about age twenty-five from the Crazy Water Crystals Company by virtue of his experience which, by that time, was considerable. Parker had worked with the Monroe Brothers and managed their band for a few years. Members of the Mountaineers now included Jenkins, Henson Stokes, Leonard Stokes and George Morris. Leonard and George, as a duo, were known as Handsome and Sambo.

In 1971, J.E. died just before an appearance at the Culpeper Bluegrass Festival. His music career spanned fifty years and he recorded over 500 songs. He died of an apparent heart attack at his home in Concord, North Carolina.

Wade received many awards through the years for his contributions to country music. Though not officially mentioned, I’m sure he accepts many of these awards with his brother in mind. Wade plays music by ear, can’t read music, and has no formal knowledge about the study of music. The duo of Wade and Julia continued to perform and record together.

Mac Wiseman—”20 Old-Time Favorites” RC-258

Liner notes by Barry R. Willis, Pine Valley Music 1997

The idea of re-releasing an old LP on compact disc has come of age. With this new technology, we fans of bluegrass music, and of its many branches, benefit tremendously. We get to hear the recording in its digital form—it’s no longer a victim of the scratches on a vinyl album, and some of the depth of the recording is not missing as a result of using some form of noise suppression as we often found with cassette tapes. We can now listen to the recording as it was presented to the microphone: a full sound with all the best qualities the recording industry could muster during that time.

Mac is one of the great pioneers of bluegrass music. This CD, however, doesn’t include his bluegrass. At the time these tunes were recorded during the 1960s, he had mostly left bluegrass to find other, more lucrative, ways of making a living in music. Mac was largely a solo performer who would use a put-together band when he performed at festivals and concerts. He was also heavily involved in the management of various record companies like Dot, RCA and CMH. He even helped found the Country Music Association during this period. He would return occasionally to record with bluegrass artists of his past, like Lester Flatt and the Osborne brothers.

Malcolm B. “Mac” Wiseman, the “voice with the heart,” was born in Crimora, Virginia, near Waynesboro in the Shenandoah valley, May 23, 1925. He was raised during the Depression on a farm where the community was poor; his father had the only wind-up phonograph and the first battery-powered radio in the community. They listened to the WLS Barn Dance and WSM’s Opry and Mac was the only musician in the family. At age eleven or twelve, Mac got his first guitar, a Sears, Roebuck, which came in the mail in a cardboard box. He had it for a year before a traveling minister tuned it for him. At age fourteen, young Wiseman sang on WSVA, Harrisonburg, Virginia, for a Future Farmers of America program. After training at the Shenandoah Conservatory of Music, Dayton, Virginia, and with a scholarship from the National Foundation for Polio, he became a DJ at WSVA. Wiseman’s first band was formed for a radio program over WFMD, Frederick, Maryland, in 1945.

Mac’s first experience in the professional music world was in Buddy Starcher’s band as an announcer. Soon he was asked to sing a few songs and was on his way to becoming a singer. The next year, Wiseman was a member of Molly O’Day and Lynn Davis’ Cumberland Mountain Folks for nine months. He was their guitar player for some time until they recorded. He recorded “Tramp on the Street”/“Six More Miles” on bass on Thanksgiving weekend. O’Day was one of the most influential people on his singing style. Wiseman considers her “the female Hank Williams of all time”. He played bass during the Columbia record sessions and appeared regularly on the Opry at this time.

In the spring of 1947, Wiseman left O’Day’s group in WNOX and went to WCYB, Bristol, Tennessee, which had recently begun operations. He played a 6 a.m. solo show where he played for free but got a percentage of what he could sell. His sponsors included insurance companies, Christmas ornaments, baby chicks and strawberry plants. The second show, the mid-day Farm and Fun Time, included his Country Boys whose members included himself (guitar), Curly Seckler (mandolin), Tex Isley (electric guitar) and Paul Prince (fiddle). The group became popular right away. He was soon busy playing school houses every evening and many afternoons. He had no records out yet.

That fall, Earl Scruggs approached Mac about a plan to quit Bill Monroe and start his own band with Chubby Wise and with Wiseman. (As far as Wiseman knew at the time, Lester Flatt had not indicated he might also leave Monroe.) There were no firm plans made at this meeting.

Wiseman soon tired of all the traveling on unpaved mountain roads choked with ice, snow, and/or mud in order to give concert at remote mining camps so he disbanded his Country Boys and moved north into Virginia. A few months later, after Scruggs and Flatt had formed their own Foggy Mountain Boys, they called Wiseman to replace Jim Eanes. Wiseman started work in the spring of 1948 on guitar, performing first in Hickory, North Carolina, and soon, with the connections he made at his earlier time at WCYB in Bristol, to WCYB’s Farm and Fun Time program. They were soon regulars with two hours daily. Wiseman also did the booking for the band which was now booked solid three months ahead. Band members were Flatt, Scruggs, Wiseman, Jim Shumate and Cedric Rainwater. In the fall, their first recordings were “My Cabin in Caroline,” “We’ll Meet Again Sweetheart,” “I’m Going to Make Heaven My Home” and “God Loves His Children.”

About Christmas time 1948, Wiseman left Flatt and Scruggs to join 50,000 watt WSB, Atlanta, on the WSB Barndance. From about this time until the mid-1950s, he toured and recorded extensively with his own Country Boys and with others. His band included many great musicians with whom he recorded some very well known bluegrass songs.

The show at WSB lasted until May so he joined Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys on the Opry. With Monroe, he recorded “Can’t You Hear Me Calling” and “Traveling This Lonesome Road.” Jimmy Martin took his place as lead singer/guitarist with Monroe at Christmas 1949.

Wiseman and his band left WCYB for the third and final time in April of 1951—this time to join KWKH’s Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport, Louisiana. On May 23rd, he began recording for Dot Records at the studios of KWKH, eventually recording his greatest hits including “Jimmy Brown, the Newsboy,” “‘Tis Sweet to Be Remembered,” “Love Letters in the Sand,” “Are You Coming Back to Me?” “I’ll Be All Smiles Tonight” and “(I’d Rather Live) By the Side of the Road.”

In April of 1952, Wiseman took his band to WDBJ, Roanoke, replacing the Bailey Brothers band which had just left for WWVA. By September, he was at WNOX on the Tennessee Barn Dance. The next year, Wiseman moved to Richmond, Virginia, after he was offered a key spot as an entertainer and at the Saturday night radio show, Old Dominion Barn Dance, which he managed until 1954. He continued to play gigs throughout North Carolina, Maryland and Virginia, touring with country favorites Jim Reeves and Hank Locklin in 1955. Mac’s recorded version of “Wabash Cannonball” was a best-seller near his home in Richmond.

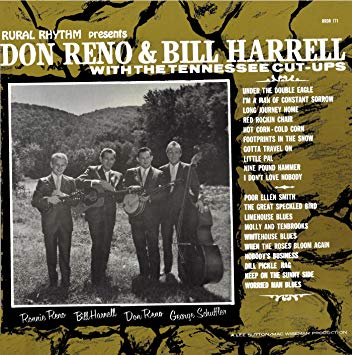

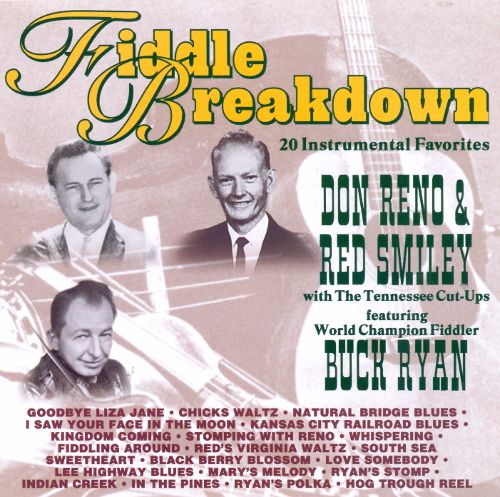

When Dot Records moved to California in 1956 after being purchased by Hollywood’s ABC-Paramount, Mac became the Director of Artists and Repertoire (A & R) for all their country music performers and ran the company’s Country Music Department. Mac disbanded his Country Boys when he moved to California. Members of his Country Boys at the time were Allen Shelton (banjo), Don Bryant, Eddie Adcock and Buck “Uncle Josh” Graves. Wiseman’s first action with Dot was to negotiate with Carlton Haney, manager of Don Reno, Red Smiley and the Tennessee Cut-Ups, to have that band sign a recording contract with Dot. This caused them to leave King Records where they had been since 1952.

In 1958, Mac Wiseman helped found the Country Music Association and became its first secretary. The next year, Mac moved from California to Nashville and became popular at folk shows for the duration of the folk music revival period (late ‘50s to early ‘60s). In about 1963, he left Dot Records to join Capitol Records. Also about this time, briefly, he had his own Wise Records. He managed WWVA’s Jamboree show from 1966 until 1970. In 1969, he left Capitol Records to join Lester Flatt in three epic recordings on RCA Records. The records were “Lester ‘N’ Mac,” “On the Southbound” and “Over the Hills to the Poorhouse.”

In 1971, Wiseman became a regular on the Renfro Valley Barn Dance, Renfro Valley, Kentucky, whose new owner was Hal Smith. During that decade, he recorded the non-bluegrass “Me and Bobby McGee,” written by Kris Kristoferson. Mac is quoted by J. Wesley Clark and J. Michael Hosfore: “There was a time when I felt switch-hitting would hurt me with bluegrass fans, but bluegrass fans are loyal and my fans are particularly loyal.” He feels that his diversity may help bring new fans to bluegrass.

On October 5, 1973, Wiseman appeared on television’s “Dean Martin Show.” October 21 was proclaimed as Mac Wiseman Day by the city of Waynesboro, Virginia, to honor its native son. July 3, 1977, was proclaimed Mac Wiseman Day by the Governor of Virginia. Wiseman was inducted into the Virginia Folk Music Hall of Fame.

Wiseman left RCA in 1974, looking for another label which promoted bluegrass music. He later ended up on CMH, owned by Arthur “Guitar Boogie” Smith and Christian Martin Haerle, which began operation in Los Angeles in 1976.

In 1986, Wiseman was a Board member of Nashville’s Reunion of Professional Entertainers (R.O.P.E.), the purpose of which was to build a retirement home for its members who are in the industry of entertainment. He served two years on the Board of the International Bluegrass Music Association. He continues to perform as a solo into the 1990s.

“31 Banjo Favorites—Volume II” RHY-268

Raymond Fairchild

Liner notes by Barry R. Willis 1999

Raymond Fairchild, half Cherokee Indian from his mother’s side, is often recognized as one of the finest bluegrass banjoists who ever lived. Some of his record projects label him “King of the Five-String Banjo,” a well deserved title.

This compact disc is the sequel to “31 Banjo Favorites” which put a gold record on Raymond’s wall at home. His other gold record is “Mama Likes Bluegrass.” Both Rural Rhythm Records projects were produced by Clarence Jackson. In addition to twenty-two instrumental tunes from “King of the Smoky Mountain Banjo Players” (RR-256) whose musicians were Raymond Fairchild (banjo), Buck Duncan (bass), Wilford Messer (fiddle) and Willie Hester (rhythm guitar), this CD includes nine tunes from two other projects already on compact disc (“16 All-Time Favorites” and “Mama Likes Bluegrass Music”). So this one, “31 Banjo Favorites—Volume II,” has the best of both worlds.

Raymond’s style is mostly his own, using the best of both Don Reno and Earl Scruggs, adding his own talents to exhibit a discernable flavor to his banjo playing. “When I leave here,” said Raymond in a 1999, “I want them to know who the banjo player was on that recording. Most of the pickers, you can’t tell who they are until that radio announcer tells you who they was.”

Raymond’s style comes from the heart. He explained it this way, “That comes from wantin’ to do somethin’ right, Barry. And that comes from not copyin’ somebody. I never did copy nobody. I went right in between Reno and Scruggs—that’s what I done. I took a path right down between ‘em. I loved ‘em both but I didn’t want to sound like them; I wanted to sound like myself. The best I can explain that to you is this: See, I was raised, we had a battery radio. And once in a while, you’d go into town and you’d see what I call a jute-box. You’d have a Reno record on there or Scruggs. You didn’t have enough money to play ‘em three or four times but you might dig up enough to play one. And you could hear some of those notes but you can’t hold a whole record in your head if you hear it one time. And I’d hold a few of them notes in my head and when I’d get home the notes I had in my head, I’d use that and I’d add mine to it. Because if I were to be where I could hear them all the time, I’d have probably copied them note-for-note.

“Bill Monroe told me himself,” continued Raymond, “he said, ‘I’m gonna tell you something. You take it with a grain of salt or anyway you want to take it. You’ve got the best timin’ of any human bein’ I ever saw.’” Powerful words from a man who definitely knows what timing is a bluegrass band should be.

Working with Rural Rhythm Records back in the 1960s and ‘70s was really quite easy, Raymond explained. Uncle “Jim O’Neal, after he got those tapes, he added a lot of stuff like piano and drums and called it ‘bottom’. That was the first recordin’. But the last four I cut with him way down in Ohio and we added all that as we cut it. That’s the way O’Neal wanted it. He proved out right ‘cause they sold; they really sold. His argument, Barry, was that if you got airplay, you had to do it commercial. He said just four bluegrass instruments was too thin. He wanted bottom like drums and piano and stuff like that. He had it right. Back then I didn’t agree with him, but now I do.”

Speaking of satisfaction, Raymond is pleased with Rural Rhythm. “I’ll tell you,” said Raymond in an unsolicited comment, “Rural Rhythm, to my notion, Barry, has the best national and international distributorship there are in the world today. Yeah. People talk about Rounder, they talk about Rebel. They don’t come nowhere in a class to that Rural Rhythm. They’ve got all the foreign markets.”

You can find Raymond and his Maggie Valley Boys every summer at the family enterprise of the Maggie Valley Opry House in Maggie Valley, NC. Raymond is also quite proud of the Fairchild Banjo designed by Raymond and built by Jimmy Cox of Topsham, Maine.