“A City of Our Own” June 1, 2001. Written for the IBMA Board of Directors.

By Barry R. Willis

Quick, name a city associate with jazz. I come up with Chicago, Portland OR, and New Orleans. Now, name a city associated with Dixieland: New Orleans comes to mind. Blues? Memphis, Chicago. Country music? Branson or Nashville.

Now, name a city associated with bluegrass. Nope, Nashville and Washington, D.C., only have a couple of venues which embrace bluegrass. Nashville couldn’t be it because it’s too involved with country music and I wonder about their motives (they’ve succeeded in destroying much of what country music should be). Washington’s association with bluegrass is of the past, not the present. Owensboro? Not really. Only IBMA people would possibly recognize the city’s association with bluegrass. It’s certainly not recognized as a bluegrass town outside our community.

Actually, then, there is no city which can be identified with bluegrass as the cities above are identified with a certain kind of music.

Bluegrass needs its own city! Thus the reason for this letter. I have some ideas on this topic and hope you will spend a few minutes with me reading this letter, then follow it up with IBMA Board members for further discussion.

In this letter we’ll discuss which city we could choose as our own and some ideas on how to do it.

To make this idea reality, we’ll have to concentrate our efforts through the IBMA; it has the organization to make this possible and I believe the idea should be a prime function of the Association. I believe the Mission Statement concurs with this idea. It reads, “The International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA) is a professional trade association dedicated to promoting and expanding the success of bluegrass music.”

Which cities might we choose? A little analysis on your part might come up with a couple candidate cities: those which might be potentially linked with our wonderful music. Nashville? Washington? Branson? Owensboro? Or even Grass Valley, California? How about Louisville?

I believe that Louisville should be our city of choice so I’ll address this discussion accordingly. I must eliminate Owensboro from the discussion for several reasons including lack of easy geographical access, convention facilities and venue infrastructure. Only the International Bluegrass Music Museum is a drawing card there, not a substantial population base or any of the other needs to make this happen.

Let’s take a cursory look at the city. Louisville is a nice, clean city with an excellent transportation system: easy access to the rest of the world by road, airlines or even river. We now hold our Trade Show and the World of Bluegrass there and plan to do so in the foreseeable future. Louisville’s WFPK has its own bluegrass show every Sunday night with local Berk Bryant as its host. Berk has been a bluegrass radio icon in the area for nearly thirty years now. The Kentucky Fried Bluegrass Festival was a part of the city for many years and many, many folks can recall attending the festival and the band contest associated with it. And Louisville is still in Kentucky, a requisite for many bluegrass aficionados who prefer to keep it in the state from which bluegrass music got its name. And I think the Louisville city planners and Chamber of Commerce would heartily embrace the idea described here.

So, how do we do it? Let’s outline a few preliminary steps—goals, if you will:

- Those involved should understand that such an idea as this one takes years to pay off, starting from this letter to the involvement of the IBMA and other organizers, then followed up by bluegrass promoters and booking agents making a concentrated effort to send bluegrass bands to Louisville. The IBMA should offer its help to Louisville in getting our bands into its town; don’t expect the town to know how to contact our bands.

- IBMA should make this a priority. We should embrace it and promote Louisville as “our” city in our promotional activities.

- When meeting with Louisville officials, the IBMA should send in its “big guns” (top officials) for this one, starting with the premise that the city is the most important factor in this idea and essential for the idea to succeed. The first meeting with these folks should at least be with our president, executive director and secretary.

- Approach not only the Chamber of Commerce of Louisville but also its clubs such as Kiwanis, Rotary, etc.. They could wield considerable power if called upon to do so.

- These above named organizations would then, in turn, contact bar owners and venue owners about this plan to have bluegrass music regularly in their town. They should be enticed to embrace this idea with all the vigor at their disposal. This is a most-critical aspect of this idea if it is to succeed.

- The Education in Schools Committee should be actively involved. Let’s start ‘em young; enable them to know and appreciate bluegrass music at an early age. By the time the kids grow up, they would actually seek the bars and other events which include bluegrass music.

- The identification of Louisville as a bluegrass city would be helped along significantly by street banners declaring that the city is now associated with bluegrass. Travel brochures would include the declaration of Louisville as a “bluegrass city.”

- Continuation of the Galt House as host of the World of Bluegrass.

After all these things have occurred, you’ll find more bluegrass books in stores and libraries, more bluegrass music for sale, more bars and restaurants signing on for a bluegrass band on a Saturday night or even for a weekday.

We may eventually see our Museum moved from Owensboro to Louisville. But since there is a lot of money and prior agreements involved between the City of Owensboro and the IBMM, this may take a long while to occur, if ever. As much as I’d like our museum to be in Louisville, it may never actually happen because of the strings attached. I wouldn’t count on this happening.

Folks, I believe the IBMA should embrace this idea as its own. If you agree, contact the Board of Directors members and discuss it with them.

Sincerely in bluegrass,

Barry R. Willis

Our Music is Changing–Whether We Like It Or Not

By Barry R. Willis 1999

There seems to be much concern about bluegrass music as it is played today. Those who may have this concern seem to adamantly prefer the traditional bluegrass styles as played by groups such as FLATT AND SCRUGGS or the BLUE GRASS BOYS or the STANLEY BROTHERS. They wish the music would stay that way. They don’t like where bluegrass has gone; how it has changed. This article will try to explain why and how our music has changed.

Let’s begin the discussion with the fact that there’s nothing wrong with preferring to hear a certain type of music–a type we grew up with which may have sentimental attachments and a certain sound to which we may have become accustomed. While it’s okay to prefer a traditional style over the newer, more progressive and intricate styles of today, we must not forget that things change with time: music changes with time; clothing styles change. It seems like everything in today’s society seems to change. Change is inevitable in life today.

Current events have a lot to do with these changes. Recall the patriotic music of World Wars I and II, the protest music of the folk era of the 1960s, and the rebellious hard rock music which began in the 1970s. And, remember how differently people dressed and how their language changed. People really do change!

We can relate these trends to people’s taste in bluegrass music as well. Remember in the mid-fifties when rock and roll music was so influential in the world? In order to make a living in this business, many name bluegrass groups–who then played traditional bluegrass–found themselves having to change their sound to compete with rock and roll. The Osbornes, Jim and Jesse, Eddie Adcock, and yes, even Flatt and Scruggs’ band changed. They may have added electric instruments and/or drums to sound more contemporary, just trying to make a living because the demand for traditional bluegrass had dried up even to the point where a fiddle was not to be found on any recording out of Nashville, the center of the recording industry.

Even today, the banjo is seldom heard on the radio. You probably recall how tremendously popular the banjo was after Earl Scruggs overwhelmed the Opry in 1946. To hear Red Allen or Bobby Osborne or Jimmy Martin tell how they had to work just for tips in the late fifties can give you an idea of how Elvis had nearly destroyed our music by driving bluegrass bands away from paying gigs. Many groups quit. Several others only played it part-time, knowing they couldn’t really earn a comfortable living at it. Package shows with both country and bluegrass stars toured to try to draw enough audience to pay their bills. A typical tour in 1960 included Ray Price, Minnie Pearl, FLATT AND SCRUGGS, Porter Wagoner, and others.

Today’s excellent example of a full-time bluegrass band who had a hard time staying with traditional bluegrass is the JOHNSON MOUNTAIN BOYS. As a full-time band, what they saved during the summer was used up in the slow, winter gig schedule. Additionally, in spite of being fully booked and one of the world’s most popular bluegrass bands, the arduous lifestyle of a touring band and lack of money were things they didn’t have to put up with–so they didn’t. Sure, there are several full-time groups out there today. But they’re just getting by. Very few love this music enough to stick it out through the years and suffer its indignities and hardships–not when they can earn a decent living outside of the music with a lot less headaches. In spite of the JOHNSON MOUNTAIN BOYS leaving the festival circuit, we should not criticize them for their decision to throw in the towel. It was not an easy choice for them, for they love this music as much as anyone. Indeed, it was a decision full of regrets, both for them and for their fans. But at least now, with their day jobs, they can have a family life, some security, and an ability to put some money aside for retirement.

Another tremendous change in this music came because of the advances which musicians have made on their particular bluegrass instrument. Bill Keith introduced the melodic style of banjo picking to us, allowing the development of another style of bluegrass. Keith’s origins for this new style was two-fold: a background in Dixieland banjo chord structures with considerable formal education along this line; and a love of old-time fiddle tunes. He developed this note-for-note-with-the-fiddle banjo picking style and revolutionized bluegrass. Both Keith’s and Scruggs’ styles are good; both are different.

And listen to Doyle Lawson’s mandolin picking. This is note-for-note-with-the-fiddle; but in a style different than Bill Monroe whose style also emulated the fiddle. Both styles are good; both are different. This analogy can be applied to other bluegrass instruments as well. The point is that our music has changed due to the technical skill of its musicians.

And song writing. While Bill Monroe may be the mentor for the writing of songs in bluegrass, many newer song writing technicians are using Monroe’s guidelines and applying them to today’s bluegrass. Bob Amos, famous songwriter for FRONT RANGE, wasn’t raised like Bill Monroe and really can’t be expected to write songs like him. Laurie Lewis, who has received much recognition for her songs, writes from a different perspective still.

The point is that music has to change. It really doesn’t have any choice because there are now different people from different skill levels and backgrounds creating it and performing it. Some may not like how it has changed, but perhaps now we understand why; and that it will change–no matter how we fight it.

Please let me reiterate that it’s okay to prefer one style of bluegrass over another. Just as we found a love for the hard-driving music of FLATT AND SCRUGGS (which is now considered as “traditional”), perhaps we may analyze this newer style of bluegrass and learn to appreciate it as well. Try to understand it; enjoy it. For it will change (evolve, if you like) whether we like it or not. If you feel this way and can’t find a concert or festival that features your kind of bluegrass, play one of your favorite records. I do!

I can best make my point by quoting from a Guest Editorial by Dick Spottswood in the May 1991 edition of Bluegrass Unlimited. Dick concludes his editorial as follows: “It’s been more than a half century since Monroe first sang “Mule Skinner Blues” at the Opry, radically altering Jimmie Rodgers’ song, itself an alteration of an older black work song. Since then, Monroe’s music has endured and prospered by precisely that kind of re-invention of traditional music themes and values. Bluegrass works because it combines the best of new and old, making the most of contemporary resources in order to validate the past. The balance between tradition and innovation is constantly shifting but always there—and bluegrass will always be exciting as long as its practicioners discover new ingredients and new ways to combine the old ones.”

The Tragedy of America on September 11th, 2001

An Article about Safety. The Crash and the Symphony. An Article about Safety.

By Barry R. Willis ALPA Council 5 Safety Chairman

Honolulu. September 11. 2001

It was such a beautiful flight over the Pacific in the middle of the night on the way home to Honolulu from Narita, Japan, on United’s flight 826. Captain Chuck Arthur and his two first officers, myself and Len Packett, had just received a silent message from Dispatch saying that there was some terrorist activity somewhere and that we should restrict our cockpit to all but the head purser.

That was simple. We could do that. Captain Arthur then began his scheduled two-hour break with the confidence that we could protect the door as ordered.

F/O Packett and I reviewed the Security chapter of our Flight Operations Manual. The part on hijacking. Good review for what could affect us if things got out of hand. But it turns out that what was to occur was not included in our Manual. We’d have to “wing” it.

The company frequency was alive with chatter. Most of it was in Japanese. Occasionally we heard the names “United” and “Delta” mentioned. Packett recalls thinking that he should have requested them to speak English so we could all share their messages.

Soon a voice in American English announced that he was being required by his company to return to Narita. We didn’t catch the name of his airline nor did we realize that something big was about to unfold. We did some quick figuring which indicated that we didn’t have enough fuel to return to our point of departure. We could stop at Midway Island, but that didn’t seem necessary at this point. No need. Yet.

Another message arrived after an hour or so. Dispatcher Sandy Reedy emphasized that NO ONE was to be allowed into the cockpit due the confirmation of terrorist activity in New York City. There was really no word to us what happened.

That was to be our last message from Dispatch. We were on our own to gather information of the unfolding events as they occurred.

We tuned into the powerful KHVH radio station out of Honolulu and continued monitoring the Company frequency to get a better idea of what was happening. As the picture became clear, we couldn’t believe it: The New York City Trade Center had been destroyed, as well as a portion of the Pentagon. What is this? A motion picture? No word from Dispatch about what had happened yet. We didn’t know yet if a United Airlines plane had been involved, but we did hear on the radio that an American Airlines flight was involved.

It was time to wake up Captain Arthur from his break.

This is the purpose of this article—an article about safety. For it is after Captain began his second shift, and Packett began his break, that things started to happen. It was a beautiful thing to watch: a well-trained and experienced Captain for United Airlines conducting the activities for his ohana—his family of pilots and flight attendants on board the Boeing 747-400 that night of tragedy. He solicited our contributions and opinions of nearly every activity and all of us involved had the impression that he not only listened to us, he actually used our inputs toward decisions which often were better than the sum of its inputs: We call this “synergy.” All decision-makers should strive toward synergy; United’s pilot training can help achieve this goal.

It was a time for patience, planning, selflessness and the execution of the result of United’s training. Captain Arthur exhibited it all. This is not an article about Captain Arthur, really, but it does reflect how United’s pilot and flight attendant training is really quite effective and up to the task of enhancing a Captain’s skills beyond what he or she may envision he/she may have. If a pilot has been paying attention, if flight attendant have been paying attention to the training, if Customer Service Representatives have paid attention to what United has taught us, then we may be able to exhibit skills far beyond the ordinary. All we have to do is do our job and be open to a little creative thinking. That means paying attention to our manuals and taking our training seriously. Captain Arthur sure did. And it showed.

But this situation was different than our training. We are trained to generally comply with terrorists and to not resist our attackers. That would be in an attempt to preserve your own life and the other lives in the airplane. We are not, however, trained to react to what happened to us. Nor to react to the scenario that the hijackers were planning to use the plane as a destructive tool: a lethal weapon full of fuel and astonishing potential for incredible damage.

Our responses to this unfolding situation caused us to rely on some of our training, but mostly our common sense. And in this process, we were forced to compartmentalize our thinking in order to think clearly.

Captain Arthur’s creative process and problem-solving capability was generally uninhibited by not having to fly the airplane. He turned that responsibility—say compartment—over to me. I tried to concentrate on this because we had some severe weather up ahead. And he gave Packett his specific orders and expected them to carried out. And Chief Purser Deedee did her job exceedingly well, too.

After a rather sparse briefing by our dispatchers (which I didn’t hear), but after listening to what his first officers had to tell him about what we had learned of the situation, Captain Arthur briefed the Chief Purser. She then left the cockpit to solicit, clandestinely, passengers who appeared to be military. She found one and moved him to the top deck close to a good defense position for the cockpit door should any attack become evident. It became apparent that Captain Arthur was analyzing every possibility and that he was planning for the worse. He kept on asking Len and me if he was acting with overkill. We supported him completely and we learned what the difference between precaution and excessive caution is. His actions led us toward the recognition that the situation might be more serious than we thought. Certainly it was more serious than Dispatch had communicated to us.

Captain also solicited the assistance of a former U.S. Army First Sergeant (Delbert, who now is a well-qualified flight attendant) to remain in our cockpit to further defend our barrier should it be broken. He was shown where the crash axe was located. Other male flight attendants (Aaron and Wayne) were also deemed as large enough to help defend our position in the cockpit and they were pressed into action.

AIRINC called. Airinc is the outfit the airlines use to voice communicate throughout the world with their planes. We were notified that all United States airports were closed except to aircraft which declare an emergency. That was one of our easiest decisions; we declared an emergency.

Was this a movie we were in? It was seeming unreal! It was not, and Captain Arthur kept on fertilizing the creative-thought processes and continued coming up with ways to solicit input from all us underlings. The synergy was rampant. We could almost see the gears turn in Arthur’s mind. Continued input led to continued creative ideas on how to handle this ever-changing situation.

Packett’s law enforcement training would become invaluable to set up a critical defense of the cockpit door should that become necessary. Get the idea? Use a person’s skills to its maximum. While the Captain and I were busy in the cockpit, Packett set up a physical defense for the cockpit door. There were suitcases used as barriers, empty wine bottles used as bludgeoning weapons, and the bad-ass attitude that if anyone should come up those stairs to the upper deck, they should treated as the enemy. He briefed the upstairs flight attendants that if anyone were to come up those stairs to the upper deck, they were to defend the cockpit “at all costs”! Packet’s words to those under his command can be paraphrased thusly: “If a person comes up those stairs, it may be with the intent to kill the pilots. You are not to simply stop them, you are to take any action necessary to keep them from getting to the cockpit door.”

To further isolate the cockpit from a potential hijacker, Captain Arthur asked that the Chief Purser DeeDee remove as many of the upper deck passengers as possible to seats away from the cockpit door. Packett and Deedee worked this “compartment,” too. She used her Japanese speaking skills to help facilitate the moving of passengers away from the area of the cockpit door. If necessary, they’d explain to the passenger that we had to move people to other seats because of the airplane’s weight and balance restrictions. None of the flight’s passengers objected. They never suspected; they didn’t expect a thing.

All the while, we debated how much information we should give to our passengers. If the passengers were to suspect that we were defending our position by publicly announcing our intentions, we feared that it might trigger one of two possible scenarios: First, if we had a terrorist on board, he might attack. Second, an announcement of that sort might trigger panic or irrational actions. We wanted neither.

It was decided to not tell the passengers anything until after landing. The last thing we needed was an emotional problem from an irrational passenger. It was agreed that Delbert would make the announcement after landing while the Captain and first officer manipulated the airplane toward the gate.

That was another excellent, synergistic decision.

Another decision we discussed was how much our Purser should tell the other flight attendants. We all kicked this idea around for a while and decided they should not know anything other than inform them of a heightened sense of hijacking and/or terrorism. They were simply told that some terrorists had done something somewhere and that they should review this area of their manuals if they had time. This worked out well. The entire crew later agreed that keeping any distractive thoughts from interfering with the work at hand–and not telling the passengers or even the other flight attendants of our situation–kept any panic or over-reacting from occurring.

After landing Captain Arthur asked Deedee to hold the flight attendants from leaving the airplane until he had a chance to de-brief them. The meeting was an explanation that we chose to keep them “in the dark” because things were unfolding so rapidly and, frankly, he wanted to avoid irrational responses to this situation. He apologized to them for not telling them more but they understood completely and were grateful that he handled the situation the way he did. Deedee then admitted that she was “in the loop” but was just too darn busy to tell everyone. That would have been an unnecessary use of her time. There was just too much to do and it would just be best if the non-critical flight attendants didn’t know. At the Captain’s meeting, they understood completely and were confident that Arthur handled the situation correctly.

After all was over and we were safe and sound on the ground, we had a chance to ask what could be done better. We wondered now if that flimsy cockpit door was really adequate for the job. And it seemed to me that security of this type would be better handled at the Airport Security level, long before they board an airplane. If that were done properly, perhaps the flimsy cockpit door would be adequate. Another thing: When Dispatch instructed us to disconnect the airphone system, I wonder if the phones should have been left available to our passengers… That way they could report to the rest of the world what’s happening to them on the airplane.

One last thought. Why did I mention a symphony? It’s because of the way Captain Arthur handled the situation. He handled the other crew members as members of an orchestra, each person playing his/her part. While we read from the music, he orchestrated the entire ensemble toward efficient accomplishment of the symphony. It was a beautiful thing. All of our Captains should be equally skilled.

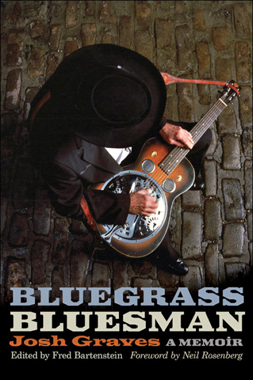

Please see Fred Bartenstein’s Bluegrass Bluesman: Josh Graves. A Memoir.

Back in 1994 I extensively interviewed Uncle Josh Graves, planning to write his biography. The plan never came to me like I’d hoped so I turned the interviews over to Fred Bartenstein whom I knew could do a great job with it.

Fred did, indeed, do a great job. He turned my interview into a wonderful work. Don’t miss this book in the University of Illinois Press stable.